ABSTRACT

Sensing the internal temperature of lithium-ion batteries is particularly useful for reliable battery operation as both electrochemistry and mass transport are dictated by local temperature. In this article, we review in operando techniques to monitor the internal temperature of lithium-ion batteries during charging and discharging. We categorize existing techniques into two groups: invasive and non-invasive approaches. Invasive techniques include optical fibers, thermocouples, and resistance temperature detectors as a thermometer. Non-invasive methods cover the temperature estimation techniques, namely electrochemical impedance spectroscopy as well as X-ray thermometry. For both approaches, we review working principle of thermometry, pros and cons of each thermometry, and recent studies to tackle relevant technical challenges. This review provides useful information for internal temperature measurements, offering chances for thermally reliable battery operation.

-

KEYWORDS: Lithium-ion battery, Optical fiber temperature sensor, Thermocouple, Resistance temperature detector, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction

-

KEYWORDS: 리튬이온 배터리, 광섬유 온도 측정기, 열전대, 저항온도측정기, 전기화학 임피던스 분광기, X-ray 회절

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries are a key element for both electrified transportation and green energy systems [

1,

2]. For reliable and safe operation of the batteries, thermal management is critically important as the temperature of the cells dictates the rate of electrochemical reactions [

3,

4], accelerates degradation [

5], and potentially leads to thermal runaway [

5-

11]. These thermal effects are more closely associated with the internal temperature, where electrochemical reactions occur. Previously, numerous studies have shown that surface measurements insufficiently capture the internal temperature, which is generally higher and spatially non-uniform [

12-

15]. This discrepancy becomes particularly pronounced during high C-rate operation, where the core temperature often exceeds the surface temperature, leading to potential degradation and thermal runaway [

16-

18]. Accurate characterization of internal temperature in batteries is critical to establish effective thermal management strategies. Given that, a variety of

in operando techniques have been developed to probe internal thermal states. This review summarizes recent advances in

in operando internal temperature measurement techniques for lithium-ion batteries, highlighting advantages, limitations, and implications for battery design and management.

In this review, we categorize internal temperature measurement techniques into two groups: invasive and non-invasive methods. This grouping is based on whether the sensing element is physically embedded within the cell architecture or the external measurements without breaking the battery sealing. Invasive approaches involve the integration of temperature sensors directly into the electrode stack. Non-invasive approaches estimate internal temperature indirectly from externally accessible parameters, such as terminal voltage, or impedance characteristics, thus avoiding physical intrusion into the cell. In this review, the section 2 and 3 cover the invasive internal temperature measurement techniques, both optical and electrical sensing, and the section 4 and 5 discuss non-invasive approaches including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and X-ray diffraction-based thermometry. Each section discusses the key operating principles of relevant thermometry techniques, summarizes performance metrics including accuracy, resolution, and stability, and outlines practical constraints. Lastly, we provide a comparative analysis of spatial resolution, accuracy, and integration challenges.

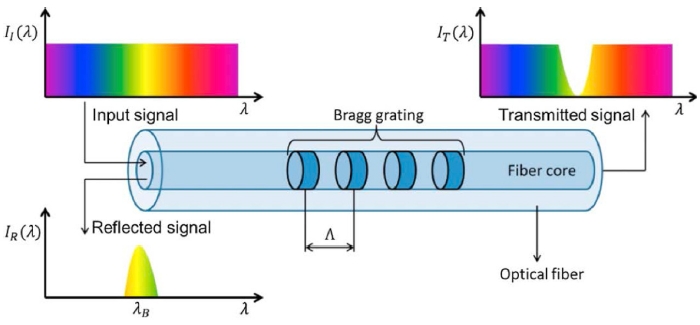

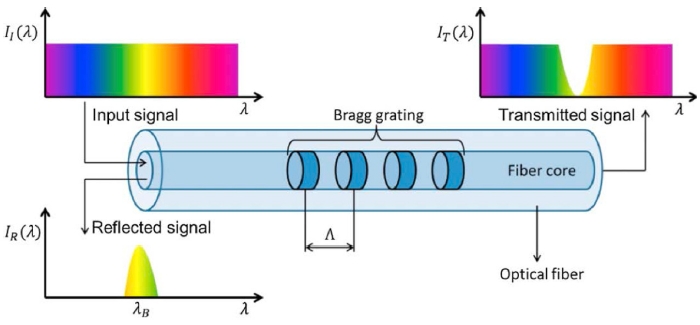

2. Invasive Methods: Optical Thermometry

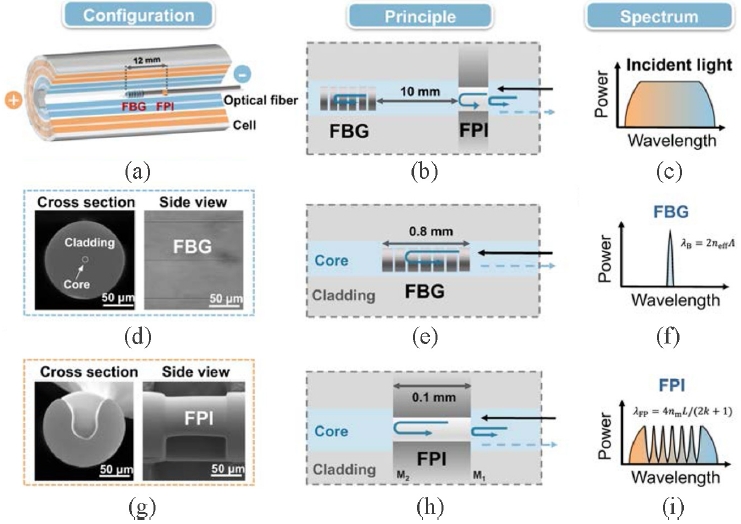

Fiber Bragg grating thermometry operates on the principle of Bragg reflection from a periodic refractive-index modulation of an optical fiber. These gratings selectively reflect a narrowband spectral component at the Bragg wavelength—defined by the relation

λB =

2neff Λ, where

neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core, and Λ is the grating period shown in

Fig. 1. The change in internal temperature induces the thermal expansion of the optical fiber, and this expansion consequently modulates its refractive index

neff. These changes lead to the shift in the reflected wavelength, expressed as

ΔλB =

λB (

α +

ξ)

ΔT, where

α is the thermal expansion coefficient, and

ξ is the thermo-optic coefficient of the fiber material [

19]. The fundamental sensing mechanism of fiber Bragg grating is based on calibrating the wavelength shift (

ΔλB) with the changes in temperature. The temperature resolution is claimed to be from ~0.1 K to ~ 0.4 K depending on sensor design and interrogation condition [

20]. In principle of Bragg reflection, in which

ΔλB shifts proportionally to local thermal expansion and refractive-index change, directly enables multiplexing of multiple gratings along a single fiber. The Bragg gratings within an ultra-thin fiber resolves multi-point temperature measurements. As the grating response is strictly localized, the intrinsic spatial resolution is estimated to be approximately 21 μm [

21]. In planar electrode configurations, this corresponds to lateral or in-plane resolution along the electrode surface, while in stacked cell architectures it represents through-thickness, or out-of-plane, resolution.

Experimental constraints arise from physical dimensions of fiber Bragg gratings: the grating lengths often extend several millimeters, limiting integration into tightly stacked electrodes such as in coin cells. In addition, fiber Bragg gratings are inherently sensitive to mechanical strain arising from electrode swelling or assembly pressure, potentially introducing experimental artifacts due to the strain. To compensate the artifacts, several strategies have been employed, including the use of reference gratings for differential strain-temperature calibration, encapsulation of the fiber in strainisolating materials, optimized sensor mounting to minimize mechanical coupling. These approaches collectively enhance the accuracy and reliability of fiber Bragg grating based temperature sensing in battery environments. In practice, compensation strategies such as differential grating pairs or compliant mechanical isolation are often required to ensure temperature fidelity.

Cylindrical cells are particularly suitable for fiber Bragg grating integration than other types of cells because the jelly-roll design of cylindrical cells provides a central path to accommodates a fiber without direct compression. The central cavity of cylindrical cells inherently provides sufficient space for fiber insertion and makes those more compatible with fiber-based sensors. This configuration overcomes the limited internal space and significant mechanical loading that restrict fiber Bragg grating placement in coin cells, hence enabling more reliable in operando temperature diagnostics. To prevent degradation from electrolyte exposure and enhance durability, fiber Bragg gratings are commonly encased within ceramic capillaries, which also provide electromagnetic shielding.

Recent studies have significantly expanded the capabilities and application scope of optical thermometry in lithium-ion batteries. Yu

et al. introduces an advanced

in operando monitoring strategy that employs embedded distributed optical fiber sensors to simultaneously capture internal structural deformation and thermal evolution within lithium-ion battery cells [

22]. In this study, local variations in temperature and strain modulate the Rayleigh backscattered spectrum, producing a measurable frequency shift (

Δν) rather than a wavelength shift. This relationship is described as

Δν =

KT ΔT +

Kεε, where

Δν is the frequency shift of the Rayleigh signal, ΔT is the local temperature change, and

ε is the mechanical strain within the electrode.

KT and

Kε are calibration constants that define the fiber’s sensitivity to temperature and strain, respectively. To separate these contributions, two complementary fibers are deployed: one strain-sensitive fiber that responds to both strain and temperature, and another mechanically isolated fiber that responds only to temperature. By comparing the two signals, the strain-induced component (

Kεε) can be subtracted, leaving only the thermal contribution (

KT ΔT). This dual-fiber configuration enables reliable decoupling of thermal and mechanical effects, thus providing accurate distributed temperature profile during cell operation.

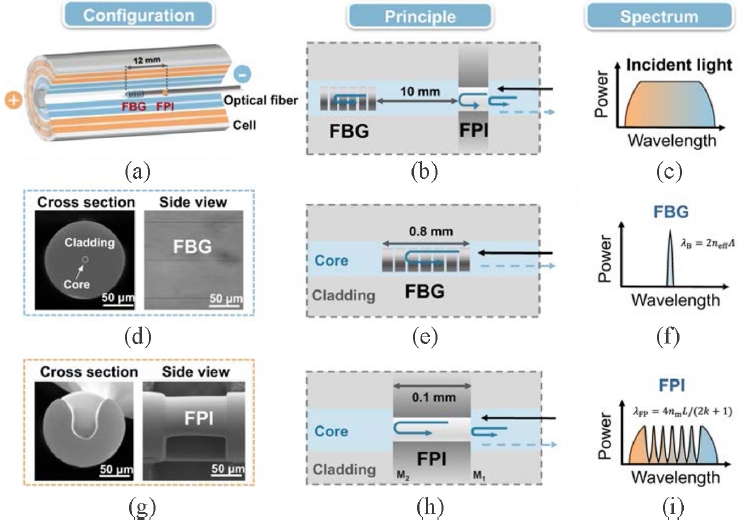

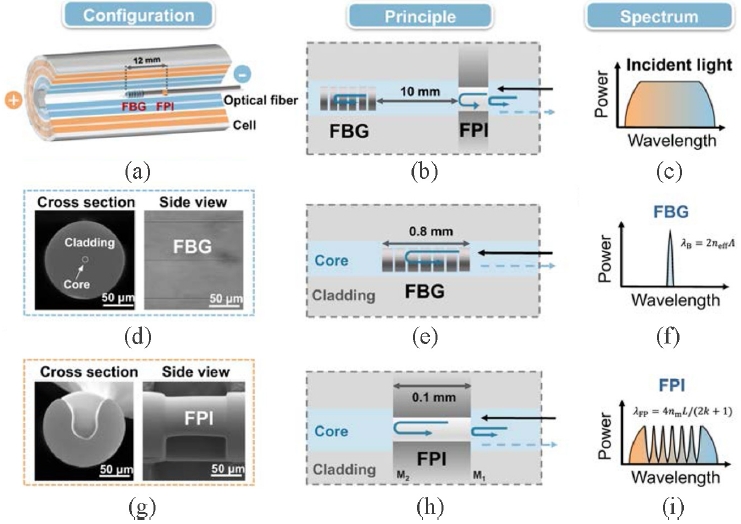

An important refinement of optical thermometry involves the development of hybrid fiber-optic sensors that allow simultaneous monitoring multiple parameters inside lithium-ion batteries. One representative approach is introduced by Mei

et al., who designed a compact sensor that integrates a femtosecond‐laser–inscribed fiber Bragg grating for temperature monitoring with a Fabry–Pérot Interferometer for pressure sensing inside 18650 cells [

23].

Fig. 2 shows the schematic of fiber Bragg grating and Fabry–Pérot Interferometer. The fiber Bragg grating element—etched directly into a 125 μm silica fiber, exhibits a highly linear wavelength‐shift response (R

2 = 0.999) across a wide thermal range 300-870 K, achieving a sensitivity of 10.3 pm K

-1 and sub-millisecond response times. Importantly, intrinsic strain compensation is achieved by engineering the fiber so that the thermo-optic coefficient

ξ and the coefficient

α oppose each other, thus increasing the refractive index while extending the grating period. During femtosecond-laser inscription, the grating geometry is optimized so that these two effects counterbalance one another, thereby minimizing the strain-induced component of the Bragg wavelength shift. This design effectively eliminates cross-sensitivity to mechanical stress and ensures stable accuracy under demanding operating conditions. Encased within a thin ceramic capillary, the sensor maintains both optical stability and chemical resilience, enabling continuous operando temperature tracking for more than 100 cycles without observable performance degradation.

Another advancement of optical thermometry is the direct embedding of flexible fiber-optic sensors inside electrode stacks to achieve stronger thermal coupling and higher fidelity of

in situ measurements. Building on this concept, Zhang

et al. extend the role of optical thermometry beyond pure thermal monitoring by embedding a flexible fiber-optic sensor directly inside pouch cells with single‐crystalline, Ni‐rich layered oxide cathodes (NCM‐SC) [

24]. Unlike conventional point sensors attached to the cell surface, this

in situ configuration enables direct thermal coupling to the electrode stack without disrupting cell operation, thus achieving an accuracy of ~0.14 K and a response time of 8 ms during dynamic cycling. This technique provides real-time access to the intrinsic heat generation of Ni-rich layered oxide cathode, allowing quantitative correlation of internal temperature excursions with polarization heat, interfacial resistance changes, and solid electrolyte interface decomposition. The key advantage of this approach is its ability to deliver highly sensitive, real-time monitoring of internal temperature evolution during charge and discharge, enabling direct correlation of thermal dynamics with electrochemical processes and offering critical insights into battery performance and safety.

Overall, fiber Bragg gratings provide an invasive yet highly precise option for

in operando thermometry, offering sub-Kelvin accuracy and spatial resolutions from sub-micrometer to millimeter scales [

20,

25-

27]. Nevertheless, sensor integration requires careful mechanical and chemical protection to avoid disturbing cell integrity, underscoring the importance of encapsulation strategies and strain-compensation schemes in achieving reliable, long-term operation.

3. Invasive Electrical Thermometry

3.1 Thermocouple

Thermocouples operate based on Seebeck effect, which is an electrical potential difference between dissimilar metal wires due to a temperature difference between a probing junction and a thermal reservoir. The conversion of the thermoelectric voltage to the temperature is expressed as

ΔV =

SΔT, where

S is the material specific Seebeck coefficient. The thermoelectric voltage is path-independent and is determined solely by the end-point temperatures, thus the thermocouples provide a robust and simple thermometry. The Seebeck coefficient

S, the key parameter of thermocouple operation, is temperature dependent, which renders the

ΔV -

ΔT relationship nonlinear and necessitates accurate calibration. Since the output represents only a temperature difference rather than an absolute value, reliable measurements require the reference junction to be measured [

28].

For appropriate temperature measurements, following conditions are essential: 1) temperature dependence and nonlinearity of the Seebeck coefficient, which necessitate calibration to ensure accuracy, 2) cold-junction compensation measurements with another thermometer, and 3) susceptibility to electromagnetic interference and thermoelectric drift, particularly under high-current operation. To mitigate these effects, calibration protocols, reference-junction monitoring, shielded wiring, and improved fabrication strategies are typically employed. With such measures in place, thermocouples achieve accuracies of up to 0.5 K, which is generally sufficient for

in operando battery diagnostics [

29].

In addition to the temperature accuracy, the practical implementation of thermocouples across different battery formats highlights both the versatility of the technique and the integration challenges specific to each cell design. The thermocouples have been implemented across different cell formats. In coin cells, the confined volume restricts sensor placement and increases the risk of disturbing electrode stacking, however, these challenges can be mitigated by using microscale thermocouples, minimizing structural disruption. In pouch cells, laminated structures are sensitive to strain, necessitating careful encapsulation of the junction. In cylindrical cells, thermocouples are commonly inserted into the jelly-roll center to obtain internal temperature data. Compared with other invasive sensors such resistance temperature detectors or fiber Bragg gratings, thermocouples are smaller, isotropic, and relatively straightforward to integrate, making thermocouples among the most versatile options for

in operando temperature monitoring across diverse battery architectures [

30-

38].

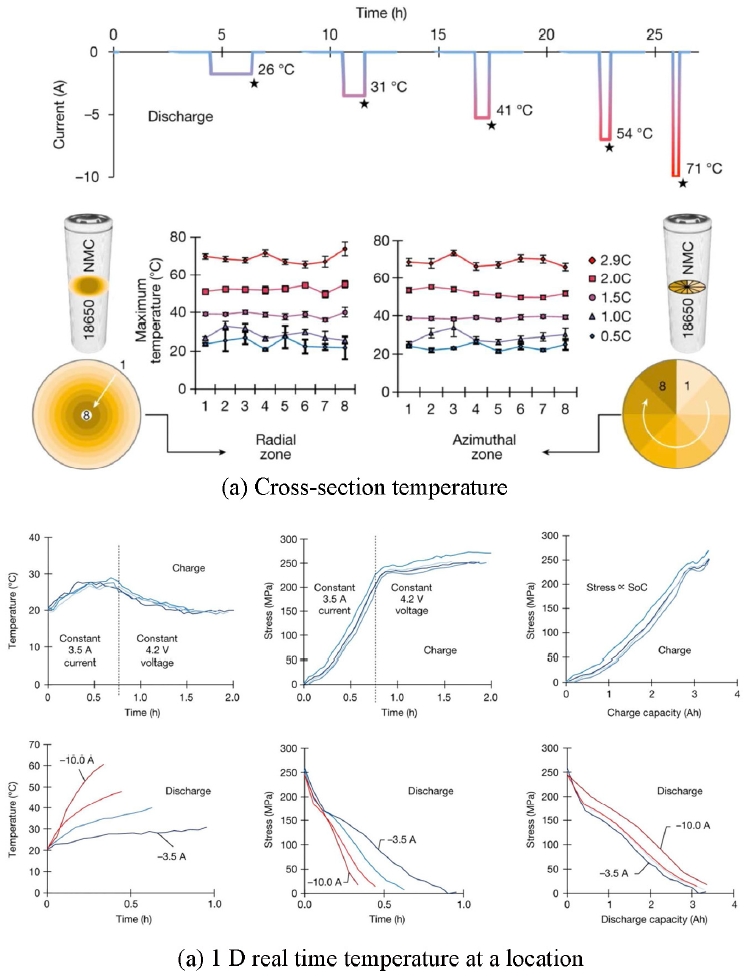

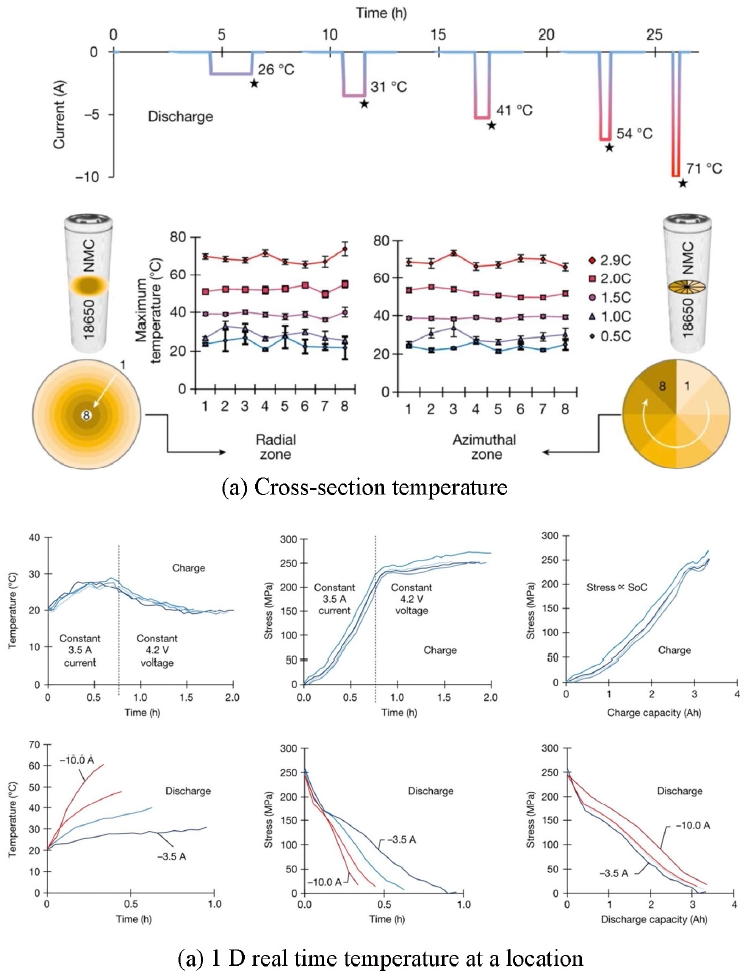

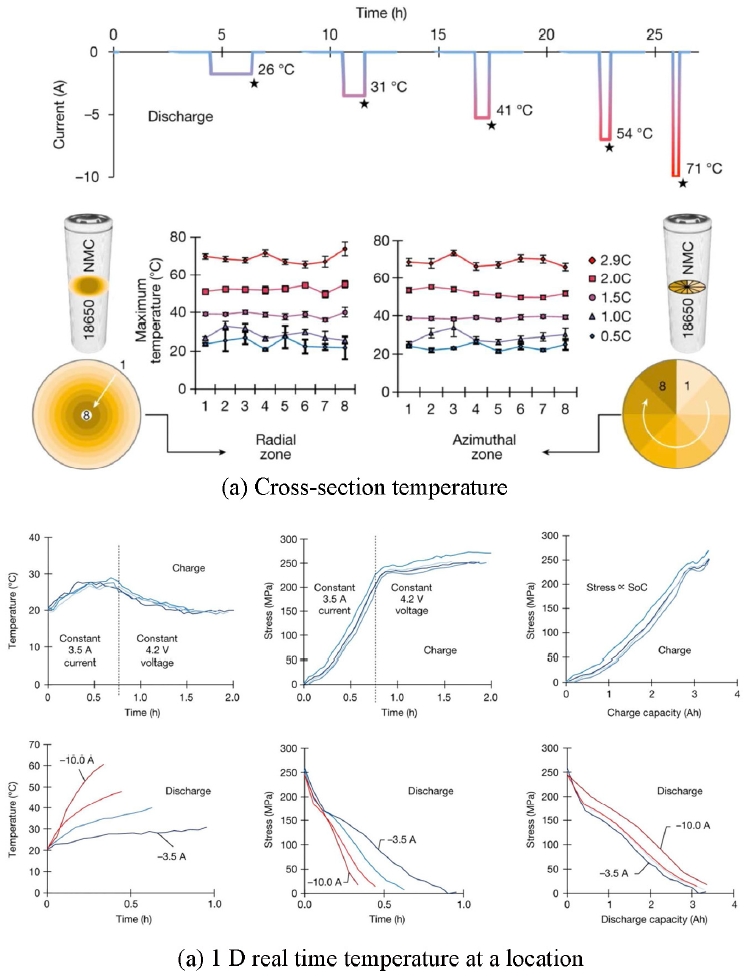

A key challenge for

in operando temperature monitoring using a thermocouple is to place ultra-thin thermocouple wires inside the jelly roll of cylindrical cells. Zhang

et al. use 0.5 mm-diameter micro-thermocouples coated with 10-μm-thick parylene, positioned at various radial positions within a commercial 18650 cell [

37]. Their measurements reveal a distinct radial temperature gradient, with the cell core consistently reaching higher temperatures than the outer layers. Moreover, their study shows that higher C-rates significantly increase both the internal temperature and its spatial variation, despite excessive cooling on its surface. Such findings provide an important reference for validating electrochemical–thermal models.

Thermocouples generally achieve accuracies within ±0.5 K [

29,

39]. Its spatial resolution is around 1 mm, which may limit the ability to resolve fine-scale heating patterns. Unlike optical fiber sensors that exhibit direct-dependent resolution, thermocouple resolution is effectively isotropic. Because it is defined primarily by the junction footprint and the thermal diffusion length, there is no intrinsic difference between lateral and through-thickness resolution.

For

in operando battery temperature monitoring, thermocouples face several limitations, including only moderate accuracy, nonlinear Seebeck response, dependence on cold-junction compensation, and susceptibility to electromagnetic interference. Among these, electromagnetic noise is particularly critical because thermocouples detect temperature through microvolt level thermoelectric voltages between two metals [

40,

41]. To address these issues, common mitigation practices include twisted-pair wiring, electromagnetic shielding, differential signal acquisition, and low-pass filtering [

42,

43]. Additionally, if the sensing junction is directly exposed to battery electrolytes, unwanted electrochemical reactions may occur, potentially compromising measurement accuracy and sensor integrity [

44]. To mitigate these issues, careful encapsulation of the thermocouple junction is essential. Encapsulation approaches are grouped into protective sleeving [

35,

36,

45,

46], and thin-film coatings such as parylene [

37,

47-

49] and polyimide (PI) [

25,

50,

51]. These protective layers not only prevent electrical and chemical interference but also maintain thermal responsiveness, hence enabling reliable localized, real-time temperature sensing

in operando battery studies.

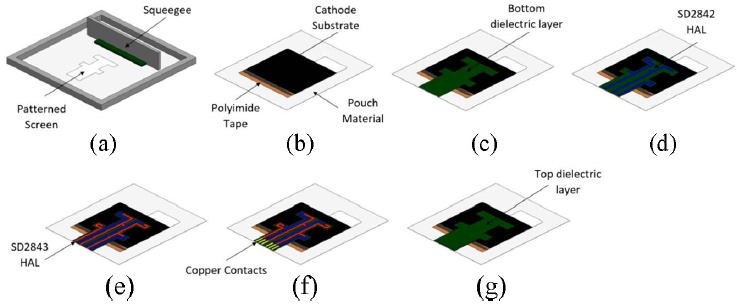

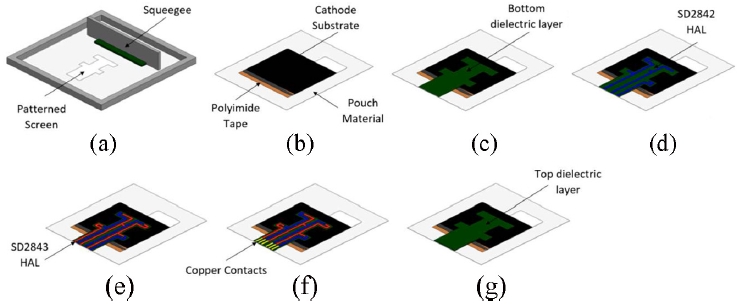

To address scalability and fabrication constrains of conventional thermocouple-based monitoring, Talplacido

et al. develop a screen-printed carbon-black thermocouple directly onto the casing of a lithium-ion pouch cell [

52]. Using an additive printing process, the carbon-black sensor is directly patterned onto the cell exterior as shown in

Fig. 3, yielding a near-linear Seebeck response, subsecond thermal response times, and stable performance over repeated charge–discharge cycles. This paper shows that such printed thermal sensors, once calibrated, can be effectively integrated into pouch cells with high sensitivity for temperature measurement. This approach highlights a potential pathway toward more scalable and practically manufacturable thermal diagnostic for lithium-ion batteries.

Resistance temperature detectors operate by exploiting the linear relationship between the electrical resistance of metals and temperature. Among various candidate materials, platinum is the most common material due to excellent reproducibility and high linearity over a broad temperature range [

53,

54]. As temperature increases, the resistance of the resistance temperature detectors element rises predictably, allowing accurate temperature estimation based on Ohm’s law. A standard platinum Pt100, for example, has

R0 = 100Ω at 0 °C (273.15 K) and a temperature coefficient α ≈ 0.00385 K

-1 such that the resistance increases by

R0 × α for each 1 K rise in temperature. In practice, a small constant current I is applied on the resistance temperature detector, and the temperature is obtained as

T =

T0 + [(

V/I-

R0)/(

αR0)] where

V is the measured voltage drop,

R0 is the resistance at reference temperature

T0, and α is the temperature coefficient of resistance [

55]. This linear relation is valid over a limited temperature range around

T0. To minimize errors introduced by lead wire resistance, four-wire configurations are used, the latter offering superior accuracy of up to ±0.01 K and long-term signal stability [

56]. Commercial resistance temperature detectors are available in compact packages with operational ranges extending from 320 to 400 K [

56,

57]. Owing to the compact and versatile form factor, resistance temperature detectors are well suited for direct integration into constrained battery environments such as coin cells or the central void of cylindrical lithium-ion cells, compared with fiber Bragg gratings, resistance temperature detectors provide a smaller footprint and greater design flexibility, making them highly attractive for battery applications.

Beyond intrinsic accuracy, the implementation of resistance temperature detectors across different battery formats highlights the versatility as well as cell specific integration challenges. In coin cells, the limited electrode stack height constrains sensor placement, but thin-film resistance temperature detectors with small footprints can be embedded without severely disturbing the lamination [

50]. In pouch cells, laminated electrodes are sensitive to strain, so careful sensor positioning is required to avoid mechanical disruption during cycling [

51]. In cylindrical cells, the central jelly-roll void offers a practical site for resistance temperature detector insertion, where the compact geometry enables minimally invasive placement for reliable internal temperature tracking [

58]. These format-specific adaptations demonstrate that resistance temperature detectors remain broadly applicable across diverse cell designs, offering greater integration flexibility than many alternative invasive sensors.

The accuracy of resistance temperature detectors is not determined solely by the intrinsic material properties but is strongly influenced by packaging and implementation factors. Key sources of error include: (1) precise determination and periodic recalibration of α over the full operating range, (2) elimination of lead-wire resistance errors through a true four-wire connection, and (3) minimal selfheating by minimizing measurement current to limit average thermal loading of the sensor [

59,

60]. In practical applications, resistance temperature detectors share several implementation characteristics with thermocouples, including the need for mechanical flexibility and chemical resilience. To avoid interference from the battery’s internal electromagnetic fields or electrochemical reactions, resistance temperature detectors are often encapsulated using polyimide (PI) films or coated with insulating layers such as epoxy or parylene [

37]. Furthermore, to enable seamless integration and further miniaturization, thin-film microfabrication techniques are increasingly adopted, particularly in Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS)-based designs [

50,

51]. These allow the creation of resistance temperature detector patterns directly onto flexible substrates or sensor platforms, enhancing both spatial resolution and durability under cycling conditions. Thin-film resistance temperature detectors can be patterned directly onto specific locations inside batteries to achieve high spatial resolutions, and the low thermal mass yields response times on the order of tens to hundreds of milliseconds [

50]. The integration of resistance temperature detector elements as thin‐film structures enables sensor thicknesses to be reduced to the sub‐micrometer scale and lateral footprints to be confined to the order of tens to hundreds of micrometers, thus facilitating high‐resolution,

in situ monitoring of local temperature distributions within compact battery cells that are inaccessible to conventionally packaged sensors [

51]. An example of this approach is presented by Lee

et al., who develop an integrated micro-sensor based on MEMS technology [

50]. This device incorporates a resistance temperature detector element that measures temperature via positive temperature coefficient of a thin metal film. The sensor is successfully embedded between the cathode and separator, and between the anode and separator, inside a commercial coin cell. The study demonstrates the sensor's high performance, achieving an accuracy better than 0.5 K and a rapid response time of less than 1 ms. This work exemplifies how miniaturized, resistance-based sensors provide a robust and effective solution for the real-time, localized monitoring of internal temperature changes in batteries with high precision and speed.

While thin-film resistance temperature detectors enable high accuracy and compact integration, the placement within dense electrode stacks often poses structural and electrochemical challenges. To address these limitations, Zhu

et al. present an

in situ, multipoint internal temperature measurement technique for lithium-ion batteries that overcomes the integration challenges of conventional sensors [

51]. By selectively etching a small cavity in the anode active material, the authors embed a 20 m thick polyimide thin film carrying platinum-based resistance temperature detector — renowned for its high accuracy, stability, and linear response—directly within the cell. This approach minimizes structural damage and capacity loss, preserving stable electrochemical performance and long-term cyclability: negligible degradation is observed even after 100 cycles. The study demonstrates that the method delivers rapid, real-time internal temperature readings that correlate closely with voltage fluctuations, offering a promising strategy for precise thermal management in advanced battery systems.

To obtain direct,

in-situ internal temperature measurements in off the shelf 18650 cells under realistic operating conditions, minimally invasive sensor-integration strategies are explored. Jones

et al. introduce a method for direct internal temperature measurement in commercially available 18650 lithium-ion batteries by strategically inserting resistance temperature sensors [

58]. Their findings indicate that while sensor integration leads to minimal impact on electrochemical performance, the modified cells largely retain the thermal behavior and trends observed in control cells, with internal temperatures being about 0.5 K higher and internal-external differences around 0.4 K. The study further demonstrates the durability of the modified cells, which are capable of operating and collecting reliable internal temperature data for 100-150 cycles before exhibiting significant degradation beyond control cells. The direct measurement strategy, particularly effective for cells with minimal cyclic aging, proves invaluable for securing critical internal thermal information. This enables more precise and comprehensive analyses of internal heating effects, the progression of degradation mechanisms, and the complex initiation of thermal runaway phenomena.

Direct patterning of microscale temperature sensors within battery architectures provides high spatial resolution and reduces disruption to electrochemical operation. MEMS-based approaches exemplify this concept, enabling resistance temperature detectors to be seamlessly embedded inside cells. Building on this principle, Ling

et al. introduce a novel

in situ temperature monitoring technique by developing a Cu/Ni alloy thin-film resistance temperature detector directly integrated with the current collector, distinguishing it from conventional resistance temperature detectors where the key advantage arises primarily from integration rather than material selection [

61]. This thin-film resistance temperature sensor is integrated between the two anode collectors, a placement that crucially avoids direct contact with electrode materials and ensures compatibility with standard battery assembly processes, thus overcoming significant limitations of conventional sensor integration. The developed thin-film resistance temperature detector demonstrates superior performance compared to commercial resistance temperature sensors, offering a faster response time and markedly higher measurement accuracy than commercial Pt1000 resistance temperature detector. This enables precise, real-time tracking of internal temperature changes across varying charge/discharge rates, such as a 1.02 K rise at a 0.5 C-rate discharge. Crucially, the insertion of this thin-film resistance temperature detector has a limited impact on battery performance, evidenced by excellent Coulombic efficiency greater than 99% and robust capacity retention of 92.71% after 100 cycles. This reliable and accurate internal temperature monitoring system provides significantly improved capabilities for preventing battery thermal runaway and enhancing overall safety.

4. Non-invasive Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measures the frequency dependent impedance of the lithium-ion cells, which is also used to measure the internal temperature of the cell non-invasively. For the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements, a harmonic perturbation in potential with a small amplitude is applied, and the frequency dependent voltage response is used to obtain a complex impedance. The corresponding impedance is expressed as the complex impedance

Z(

ω) =

V(

ω)/

I(

ω) =

Z′(

ω) +

jZ′′(

ω), where

Z′ and

Z′′ denote the real and imaginary components of the impedance, respectively, and

ω is the angular frequency [

63].

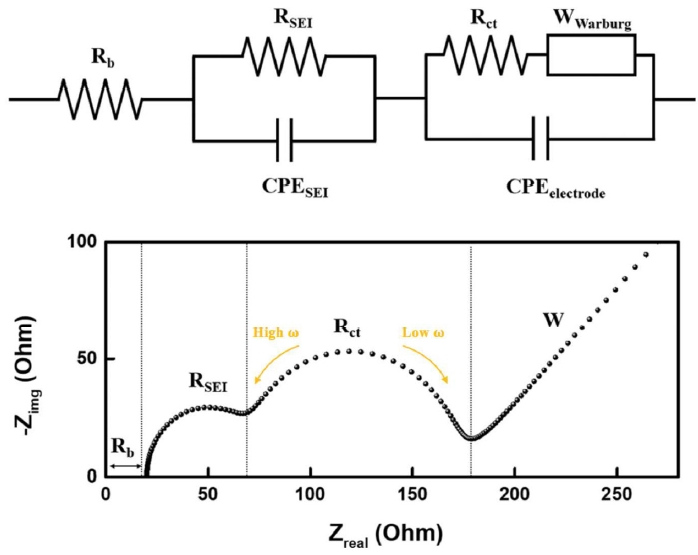

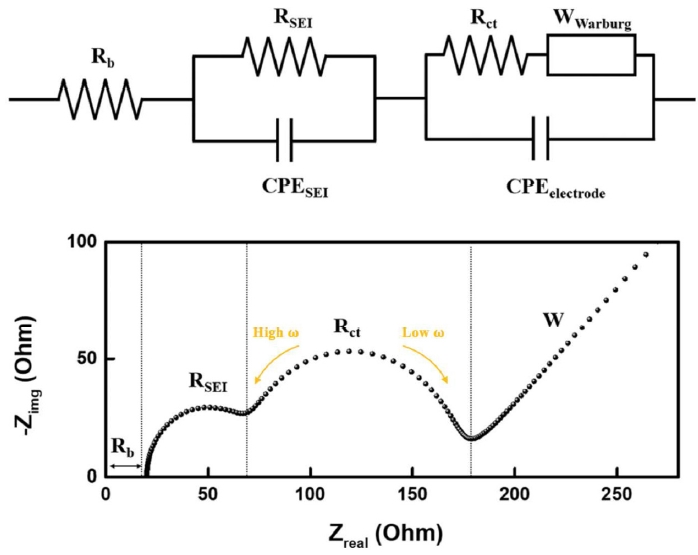

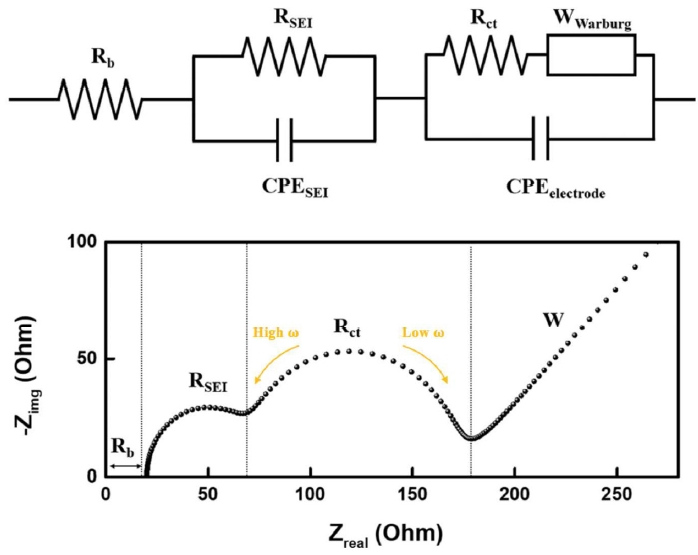

A typical response of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy shows various regimes, which are associated with specific physicochemical processes. Specifically, the high-frequency intercept reflects electrolyte and current-collector resistance, the mid-frequency semicircle arises from charge-transfer and double-layer/solid electrolyte interface dynamics, and the low-frequency tail corresponds to diffusion-controlled processes, Warburg impedance [

62-

64].

As abovementioned processes are strongly associated with temperatures, the impedance of those zones shows temperature dependence. At high frequencies from 100 kHz to 10 kHz, the bulk resistance

Rb decreases with rising temperature owing to enhanced ionic conductivity. In the high-to-mid frequency range, the interfacial resistance

RSEI reflects the thermal stability and composition of the solid electrolyte interphase. In the mid-frequency ranges from 10 kHz to 10 Hz, the charge-transfer resistance

Rct is most sensitive to temperature because interfacial reaction kinetics are strongly thermally activated, indeed, at low temperatures below 20 ℃,

Rct dominates the total cell resistance. In the low frequency regime from 10 Hz to 10 mHz, the Warburg impedance captures solid-state diffusion of lithium ions, where the diffusion coefficient follows an Arrhenius-type relation with temperature.

Fig. 4 presents these frequency ranges and model of the internal structures [

65,

66]. These systematic temperature dependencies provide the relational for employing electrochemical impedance spectroscopy as a thermal probe.

To establish a quantitative relationship between impedance features and absolute internal temperature, calibration procedures are essential. Typically, cells are placed in a temperature-controlled chamber under well-defined, stable conditions, and impedance spectra are measured across a range of known temperatures. By correlating selected impedance features such as phase angle, charge-transfer resistance, or high frequency intercept with chamber temperature, empirical calibration curves are established [

65,

66]. This approach implicitly assumes a uniform internal temperature distribution, which may not strictly hold under practical cycling where thermal gradients develop [

67]. As a result, calibration remains cell-specific and condition-dependent, with accuracy depending on both the chosen frequency window and the validity of the uniform-temperature assumption.

A critical aspect of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based thermometry is the careful selection of frequency windows, since different impedance regimes exhibit varying sensitivity to temperature, state of charge, and diffusion-related processes. Srinivasan

et al. demonstrate a direct correlation between the internal temperature of rechargeable lithium-ion cells and the phase angle of the impedance [

65]. Across multiple cell formats tested in the 253-339 K range, they identify an optimal frequency window of 40-100 Hz, where the phase angle is governed almost exclusively by temperature and remains largely independent of state of charge and state of health. This behavior is attributed to the temperature-sensitive ionic conduction within the solid electrolyte interphase layer. This frequency range is specifically chosen because frequencies lower than this window are dominated by charge-transfer and diffusion processes that strongly couple to state of charge, while frequencies higher than this window increasingly reflect electrolyte resistance with reduced sensitivity to interfacial kinetics. Within this intermediate band, the phase angle is primarily dictated by temperature sensitive ionic conduction with the solid electrolyte interphase.

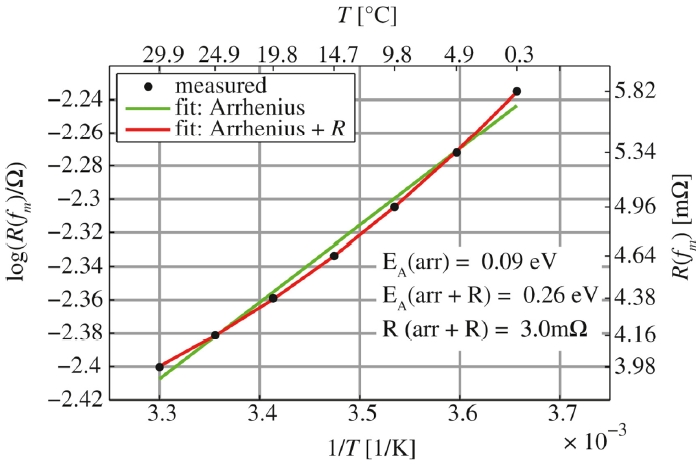

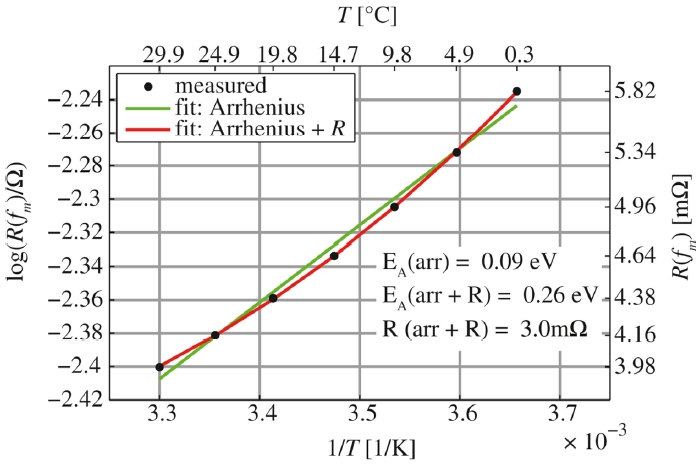

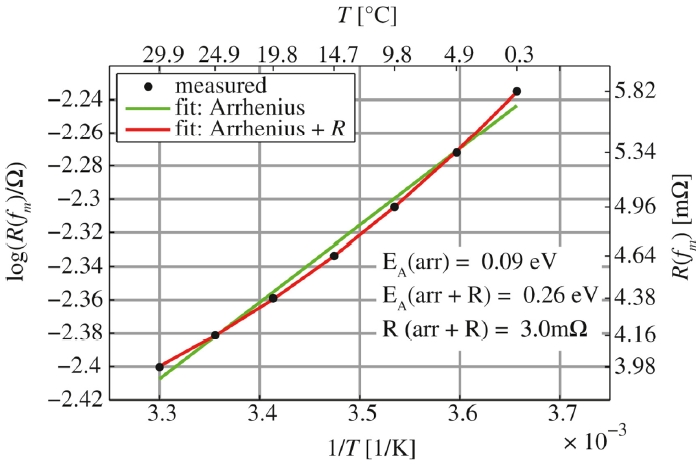

A complementary strategy within impedance-based thermometry is to exploit the high-frequency regime, where electrolyte resistance dominates, and temperature sensitivity is pronounced. Schmidt

et al. advance the impedance-based thermometry method by calibrating the real part of the impedance at a selected high frequency of 10.3 kHz against internal temperature [

66]. This frequency is selected because it falls within a regime where the ohmic resistance of the electrolyte dominates, rendering the response strongly temperature-dependent while minimally affected by state of charge. At even higher frequencies, inductive artifacts from current collectors and wiring become significant, while at lower frequencies interfacial processes introduce state of charge dependence. The authors fit the temperature dependence with a modified Arrhenius-type equation that includes an additional constant resistance term to account for current collector contributions, thus improving accuracy shown in

Fig. 5. Incorporating state of charge dependence into calibration, the method achieves sub-Kelvin accuracy when state of charge is known.

Beyond methodological advances, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based thermometry also faces practical implementation challenges. First accurate use demands calibration adapted to the particular battery type, as the impedance-temperature correlation varies with design and state of health [

66]. Second, the technique inherently provides only averaged temperature information and lacks spatial resolution, which limits its ability to detect localized heating areas that often trigger degradation or thermal runaway [

68]. These challenges emphasize that while electrochemical impedance spectroscopy is powerful non-invasive probe, its utility for battery management systems depends critically on careful calibration, model coupling, and interpretation tailored to specific cell designs.

To overcome the limitation of the uniform-temperature assumption inherent in calibration-based methods, Richardson

et al. develop a thermal-impedance model that links electrochemical impedance measurements with a radial heat transfer framework [

67]. The cell is represented as concentric annuli connected in parallel, and the overall admittance at a single frequency is expressed as the integral of local temperature-dependent admittivity. Impedance is periodically measured at 215 Hz –a frequency deliberately chosen because it provides strong sensitivity to temperature while being largely insensitive to state of charge. At lower frequencies, state of charge-dependent charge-transfer and diffusion effects dominate, whereas at higher frequencies the response is governed by bulk electrolyte resistance, limiting spatial sensitivity. At 215 Hz, the real-impedance component maps directly onto the cylindrical heat equation, enabling radial temperature reconstruction under surface-boundary constraints. Validation using a 26650 cell instrumented with an internal thermocouple under current pulses and an automotive drive cycle shows that the method estimates core temperature with a mean error of 0.6 K, compared with 2.6 K when uniform temperature is assumed. This demonstrates that targeted frequency selection, in conjunction with thermal modeling, enables spatially resolved internal temperature estimation under realistic operating conditions.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based temperature estimation also has inherent limitations. The correlation between impedance features and temperature is not universal and typically requires calibration tailored to each cell design, chemistry, and aging condition. Moreover, while the technique effectively tracks average internal temperature trends, it provides limited insight into spatial distribution or localized hot spots. This lack of spatial specificity becomes particularly critical in large-format or high-power cells, where uneven heating may compromise both performance and safety.

Building on these limitations, subsequent studies refine electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based thermometry into sensor-less strategies for real-time monitoring [

19,

65,

66]. Low-amplitude perturbations combined with rapid impedance acquisition enable continuous temperature inference under dynamic conditions. Integration with Kalman filters and Arrhenius-parameterized equivalent-circuit models further enhance accuracy by reducing measurement noise, capturing transient dynamics, and incorporating the intrinsic thermal dependence of electrochemical processes.

In summary, despite these limitations such as the need for cell-specific calibration and the lack of spatial resolution, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy remains a versatile and non-destructive tool for estimating internal temperatures of batteries. Its non-intrusive implementation-requiring no embedded sensors-eliminates concerns over chemical compatibility, mechanical disruption, and space constraints. These advantages make electrochemical impedance spectroscopy particularly attractive for practical development across a wide range of battery formats, especially when integrated with complementary modeling or estimation strategies in battery management system [

66,

68-

73].

5. Non-invasive X-ray Based Thermometry

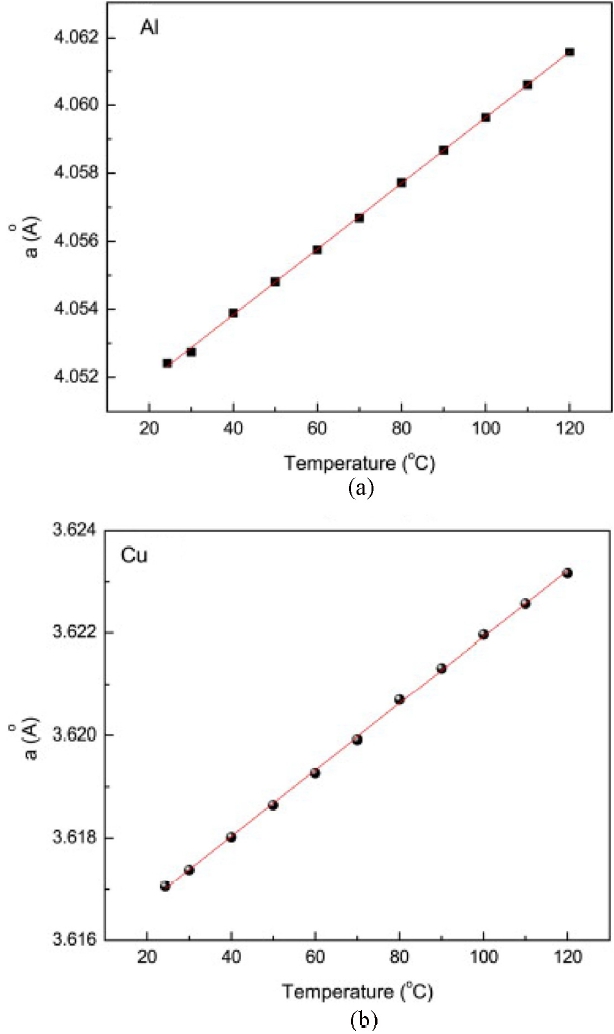

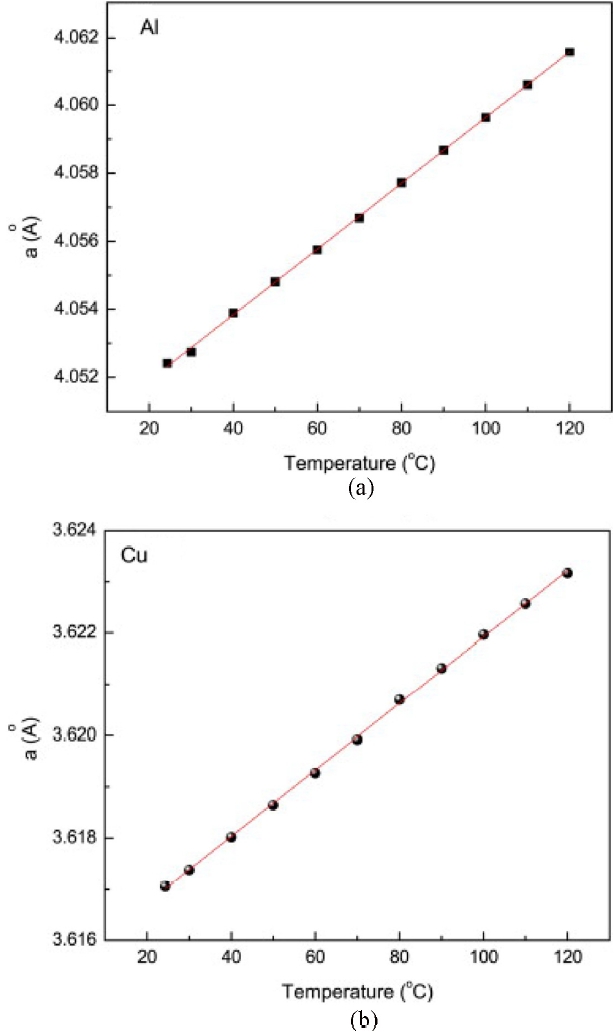

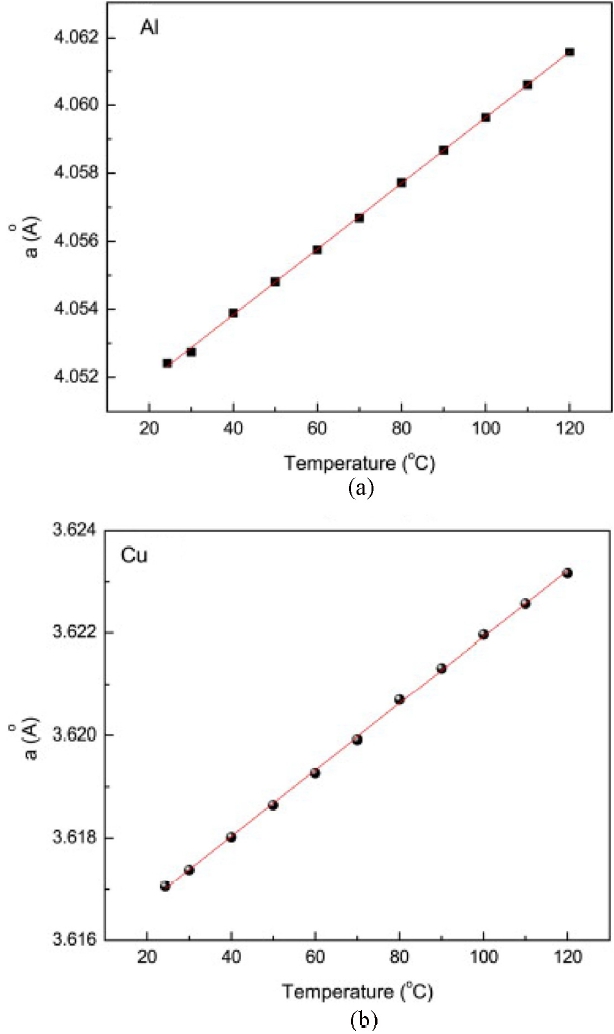

High-energy X-ray diffraction is a non-invasive technique to obtain spatially resolved temperature distribution in lithium-ion batteries. This method uses the thermal expansion of a current collectors, specifically a copper at the anode and an aluminum at the cathode. As the temperature of a cell rises, the interplanar spacing d increases, shifting diffraction peak positions according to Bragg’s law (

nλ =

2d sinθ) [

74-

78]. By tracking the peak shifts during charging-discharging, electrode-specific temperature can be quantitatively extracted. Spatial resolution is determined by scanning a collimated high-energy X-ray diffraction beam and reconstructing X-ray diffraction patterns into 2D temperature maps with parallel/perpendicular to the beam [

79].

Accurate quantification requires prior calibration of the thermal expansion behavior of the current collectors. Typically, lattice spacing shifts of Cu and Al are measured under isothermal conditions across a defined temperature range, establishing empirical relations between d-spacing and absolute temperature. These calibration curves provide the basis for operando applications during cycling.

A major challenge for high-energy X-ray diffraction studies is to extract electrode-specific thermal behavior during dynamic cycling, where different degradation pathways may give rise to highly asymmetric heating. Within this context, Lin

et al. first demonstrate the feasibility of high-energy X-ray diffraction for

in operando thermal monitoring in a commercial 18650 cell during overcharge, revealing a distinct electrode level thermal divergence as shown in

Fig. 6 [

74]. A key finding of their study is the distinct thermal divergence between electrodes during overcharge: while the cathode temperature began rising near 4.16 V due to a phase transition (H

2→H

3) in the layered LiNi

0.8Co

0.15Al

0.05O

2 (NCA) material, the anode exhibits delayed but abrupt heating beyond 4.58 V, attributed to exothermic reactions between deposited lithium and the organic electrolyte. This crystallographic resolved thermal tracking provides critical insight into electrode-level degradation pathways and helps elucidate the sequence of failure events that lead to thermal runaway.

An important advancement of high-energy X-ray diffraction is its extension beyond structural analysis to enable simultaneous mapping of local temperature, state of charge, and mechanical strain in operating cells. Yu

et al. pioneer this approach in a commercial Li-ion pouch cell without embedding intrusive sensors [

80], thereby expanding the application of X-ray techniques beyond conventional structural analysis to encompass thermal and electrochemical diagnostics. In this method, real-time measurements of lattice-spacing changes (

Δd/d, relative change in interplanar spacing) encapsulate three concurrent contributions—chemical strain from lithiation, thermal strain from temperature fluctuations, and mechanical strain from applied stresses or deformations. Since Cu and Al current collectors do not undergo lithiation during battery cycling, the measured relative

d-spacing change (

Δd/d) arises solely from thermal expansion and mechanical deformation. The authors first perform isothermal charging at fixed temperature to establish the mechanical-strain baseline, then conduct constant-state of charge heating to extract the effective thermal-expansion coefficient of each collector. By subtracting the mechanical contribution and applying the measured thermal coefficient to the residual lattice shift, they calculate the internal temperature rise. Interestingly, the mechanical strain baseline proves largely invariant to both charging rate and operating temperature, simplifying the decoupling process across a wide range of conditions.

Furthermore, with appropriate tomographic reconstruction, the high-energy X-ray diffraction approach extends beyond line-of-sight measurements to estimate centerline temperatures and ultimately generate full 3D maps of the cell’s internal thermal field. Heenan

et al. introduce a powerful methodology for the non-destructive analysis of the internal thermal and mechanical behavior of commercial lithium-ion batteries using a combination of advanced synchrotron X-ray diffraction techniques, including X-ray diffraction-computed tomography and multi-channel collimator X-ray diffraction [

79]. They adopt synchrotron radiation high-energy X-ray diffraction to obtain spatial mapping and to decouple thermal and mechanical lattice strains. This is achieved by exploiting the directional sensitivity of multi-channel collimator-X-ray diffraction and the spatial reconstruction capability of diffraction-computed tomography. The lattice parameters of metallic current collectors are extracted with high angular precision under

operando cycling. Tracking thermal strain enables the generation of detailed 2D temperature maps and measurement of real-time temperature fluctuations inside the cell, revealing that the C-rate is the dominant factor in temperature rise, far outweighing minor spatial gradients within the battery's jelly roll as shown in

Fig. 7. The

operando measurements further demonstrate how charging protocols directly influence heat generation, with temperature rising during the constant current phase due to Joule heating and dropping during the constant voltage phase. This work provides the importance of monitoring both thermal and mechanical strain for validating battery models and enhancing safety, particularly in degraded cells where increased resistance leads to higher temperatures.

A major advantage of high-energy X-ray diffraction is that it is entirely external to the cell, eliminating the need for embedded sensors and avoiding concerns about chemical compatibility, mechanical disruption, or internal space constraints [

74,

81]. It also offers electrode-level specificity and micron-scale spatial resolution along the X-ray beam path, enabling direct linkage between crystallographic changes and localized temperature evolution [

74,

79]. However, accuracy depends on material-specific calibration and the clarity of diffraction signals, which vary with electrode composition [

81]. Moreover, high-energy X-ray diffraction inherently provides line-of-sight rather than volumetric mapping, limiting spatial completeness in heterogeneous or large-format cells [

79]. Furthermore, operando implementation requires access to high-brilliance synchrotron sources, restricting scalability for routine applications [

79,

82]. These constraints underscore that while high-energy X-ray diffraction provides exceptional mechanistic insight, its broader deployment for battery thermal management will rely on complementary modeling frameworks and advances in laboratory-scale X-ray instrumentation [

82].

6. Conclusion

Internal temperature monitoring is critical to ensure the safe, efficient, and durable operation of lithium-ion batteries, particularly under demanding conditions. This review has comprehensively examined both invasive and non-invasive methodologies for internal temperature assessment, highlighting the operating principles, technical advantages, and limitations.

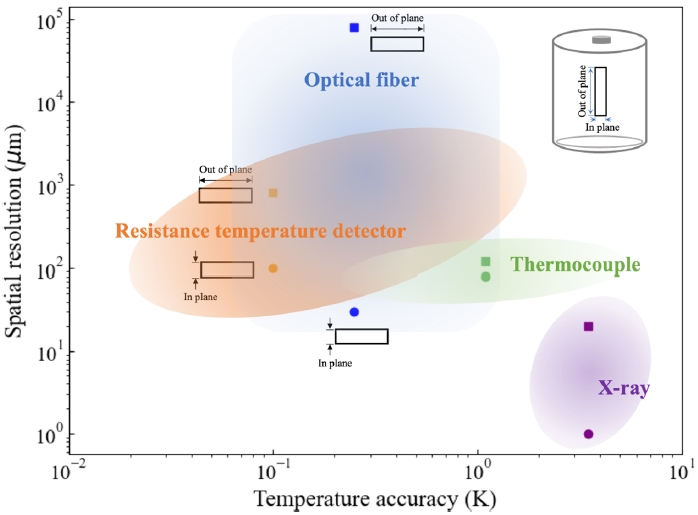

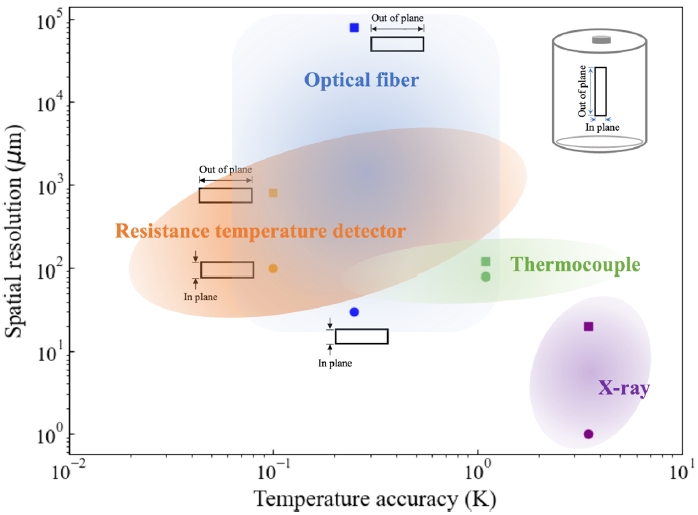

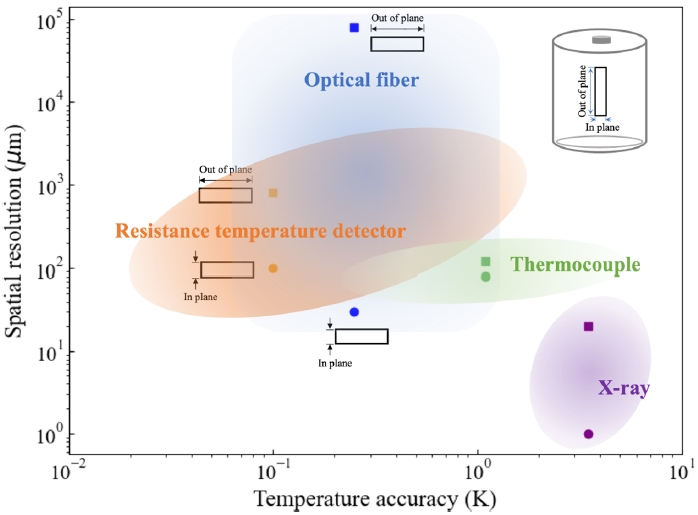

Fig. 8 summarizes key metrics for the thermometry temperature accuracy and spatial resolution for the thermometry covered in this review. Optical fiber thermometry, particularly fiber Bragg gratings, reports temperature uncertainties on the order of ~0.1 K and up to ~0.4 K depending on strain compensation and optical readout conditions [

20], with spatial resolutions ranging from a few micrometers – set by the optical sampling volume – to millimeter scales along the fiber path [

21]. For thermocouples, reported temperature uncertainty ranges from approximately 0.5 K [

29] to about 2.5 K when embedded and read out

in operando within commercial lithium ion batteries [

39], and the effective error approaches a few kelvin, that is, around 2-3 K, under more demanding conditions. The achievable spatial resolution is on the order of 1 mm, determined primarily by the junction size and local thermal diffusion. Resistance temperature detectors typically achieve sub-kelvin internal thermometry. Thin film platinum resistance temperature detectors driven and read out through calibrated four wire electronics report temperature uncertainties down to ~0.01 K [

83]. When these thin-film resistance temperature detectors are embedded directly into commercial lithium-ion batteries and operated

in situ during cycling, additional electrical and thermal noise increases the effective error to ~0.5 K [

51,

56,

83,

84]. Resistance temperature detectors are typically implemented with lateral dimensions ranging from hundreds of micrometers to a few millimeters, enabling integration into confined regions such as coin-cells or the central region of cylindrical formats [

51,

56,

57,

83-

85]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy achieves temperature uncertainties as low as ~0.2 K [

66], but errors rise to several kelvin in less constrained, model-free implementations or in cells with strong internal gradients [

66,

68-

72,

86]. High-energy synchrotron X-ray based thermometry demonstrates ~0.1 K sensitivity, with effective spatial resolution of a few micrometers set by the X-ray probe volume and tomographic reconstruction rather than by a physical sensor footprint [

79,

87-

91]. These quantitative comparisons highlight the trade-offs between resolution, accuracy, and integration complexity, reinforcing the need for hybrid sensing strategies in next-generation battery systems.

Invasive sensing techniques include fiber Bragg gratings, thermocouples, and resistance temperature detectors, providing direct access to high-resolution thermal data. Recent studies show the integration of invasive sensors into commercial batteries with minimal impact on cell performance. Still, remaining challenges are integration complexity, structural intrusion, and long-term stability. Non-invasive strategies such as the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and the X-ray based thermometry provide internal temperature information without physically altering the cell architecture. The remaining challenges for the invasive methods are complex instrumentation, extensive calibration, and limited scalability.

FOOTNOTES

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00218255 and RS-2024-00351192) and Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) (No. 20212020800090).

Fig. 1Optical fiber sensor schematic [

19] (Adapted from Ref. 19 with permission)

Fig. 2Fiber Bragg grating and Fabry-Pérot Interferometer configuration [

23] (Adapted from Ref. 23 on the basis of OA)

Fig. 3Carbon-black sensor [

52] (Adapted from Ref. 52 on the basis of OA)

Fig. 4Equivalent circuit model of a lithium-ion half-cell from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy [

62] (Adapted from Ref. 62 on the basis of OA)

Fig. 5The real component of impedance at 10.3 kHz evaluated at 50% state of charge. Fits are shown for the Arrhenius equation (green line) and an added ohmic resistance (red line) [

66] (Adapted from Ref. 66 with permission)

Fig. 6Temperature dependence of the cubic lattice parameter α for (a) Al and (b) Cu, showing an approximately linear relation over the measured range [

74] (Adapted from Ref. 74 with permission)

Fig. 7Diffraction-based internal thermometry in a commercial 18650 (a) X-ray diffraction computed tomography during high rate discharge current, peak temperature at the open-circuit transition, and 8 zone temperature maps (b) Multi-channel collimator Xray diffraction: temperature and stress during charge/discharge over four cycles, and state of charge-stress relations [

79] (Adapted from Ref. 79 with permission)

Fig. 8Quantitative comparison of invasive methods such as thermocouples, resistance temperature detectors, optical fibers, and non-invasive such as X-ray thermometry for internal temperature monitoring in lithium-ion batteries. The horizontal axis represents achievable temperature accuracy, while the vertical axis indicates spatial resolution. Shaded regions illustrate the typical performance ranges of each method, highlighting trade-offs between accuracy and resolution. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy is excluded from this comparison because it estimates internal temperature indirectly rather than providing direct spatially resolved measurements

REFERENCES

- 1. Diouf, B., and Pode, R., (2015), Potential of lithium-ion batteries in renewable energy, Renewable Energy, 76, 375-380.

- 2. Opitz, A., Badami, P., Shen, L., Vignarooban, K., and Kannan, A. M., (2017), Can Li-ion batteries be the panacea for automotive applications?, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 68, 685-692.

- 3. Ji, Y., Zhang, Y., and Wang, C.-Y., (2013), Li-ion cell operation at low temperatures, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 160(4), A636.

- 4. Ma, S., Jiang, M., Tao, P., Song, C., Wu, J., Wang, J., Deng, T., and Shang, W., (2018), Temperature effect and thermal impact in lithium-ion batteries: A review, Progress in Natural Science: Materials International, 28(6), 653-666.

- 5. Lyu, P., Liu, X., Qu, J., Zhao, J., Huo, Y., Qu, Z., and Rao, Z., (2020), Recent advances of thermal safety of lithium ion battery for energy storage, Energy Storage Materials, 31, 195-220.

- 6. Spotnitz, R., and Franklin, J., (2003), Abuse behavior of high-power, lithium-ion cells, Journal of Power Sources, 113(1), 81-100.

- 7. Bandhauer, T. M., Garimella, S., and Fuller, T. F., (2011), A critical review of thermal issues in lithium-ion batteries, Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 158(3), R1.

- 8. Lopez, C. F., Jeevarajan, J. A., and Mukherjee, P. P., (2015), Characterization of lithium-ion battery thermal abuse behavior using experimental and computational analysis, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 162(10), A2163.

- 9. Kong, D., Zhao, H., Ping, P., Zhang, Y., and Wang, G., (2023), Effect of low temperature on thermal runaway and fire behaviors of 18650 lithium-ion battery: A comprehensive experimental study, Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 174, 448-459.

- 10. Duh, Y.-S., Sun, Y., Lin, X., Zheng, J., Wang, M., Wang, Y., Lin, X., Jiang, X., Zheng, Z., and Zheng, S., (2021), Characterization on thermal runaway of commercial 18650 lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles: A review, Journal of Energy Storage, 41, 102888.

- 11. Parhizi, M., Ahmed, M., and Jain, A., (2017), Determination of the core temperature of a Li-ion cell during thermal runaway, Journal of Power Sources, 370, 27-35.

- 12. Alujjage, A. S., Vishnugopi, B. S., Karmakar, A., Magee, D. P., Barsukov, Y., and Mukherjee, P. P., (2025), Internal temperature evolution metrology and analytics in Li‐ion cells, Advanced Functional Materials, 2417273.

- 13. Yang, X., Gao, X., Zhang, F., Luo, W., and Duan, Y., (2021), Experimental study on temperature difference between the interior and surface of li [Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3] O2 prismatic lithium-ion batteries at natural convection and adiabatic condition, Applied Thermal Engineering, 190, 116746.

- 14. Wang, X., Zhu, J., Liu, D., Liu, Q., Jiang, Y., Wang, X., Liu, H., Tao, S., Wei, X., and Schade, W., (2025), Internal temperature evolution of lithium-ion battery over long-term cycling via advanced fiber sensing, Journal of Power Sources, 652, 237604.

- 15. Jinasena, A., Spitthoff, L., Wahl, M. S., Lamb, J. J., Shearing, P. R., Strømman, A. H., and Burheim, O. S., (2022), Online internal temperature sensors in lithium-ion batteries: State-of-the-art and future trends, Frontiers in Chemical Engineering, 4, 804704.

- 16. Ren, D., Feng, X., Lu, L., Ouyang, M., Zheng, S., Li, J., and He, X., (2017), An electrochemical-thermal coupled overcharge-to-thermal-runaway model for lithium ion battery, Journal of Power Sources, 364, 328-340.

- 17. Li, S., Zhang, C., Zhao, Y., Offer, G. J., and Marinescu, M., (2023), Effect of thermal gradients on inhomogeneous degradation in lithium-ion batteries, Communications Engineering, 2(1), 74.

- 18. Lin, J., Chu, H. N., Howey, D. A., and Monroe, C. W., (2022), Multiscale coupling of surface temperature with solid diffusion in large lithium-ion pouch cells, Communications Engineering, 1(1), 1.

- 19. Raijmakers, L., Danilov, D., Eichel, R.-A., and Notten, P., (2019), A review on various temperature-indication methods for Li-ion batteries, Applied Energy, 240, 918-945.

- 20. Mikolajek, M., Martinek, R., Koziorek, J., Hejduk, S., Vitasek, J., Vanderka, A., Poboril, R., Vasinek, V., and Hercik, R., (2020), Temperature measurement using optical fiber methods: Overview and evaluation, Journal of Sensors, 2020(1), 8831332.

- 21. Guo, Z., Han, G., Yan, J., Greenwood, D., Marco, J., and Yu, Y., (2021), Ultimate spatial resolution realisation in optical frequency domain reflectometry with equal frequency resampling, Sensors, 21(14), 4632.

- 22. Yu, Y., Vincent, T., Sansom, J., Greenwood, D., and Marco, J., (2022), Distributed internal thermal monitoring of lithium ion batteries with fibre sensors, Journal of Energy Storage, 50, 104291.

- 23. Mei, W., Liu, Z., Wang, C., Wu, C., Liu, Y., Liu, P., Xia, X., Xue, X., Han, X., and Sun, J., (2023), Operando monitoring of thermal runaway in commercial lithium-ion cells via advanced lab-onfiber technologies, Nature Communications, 14(1), 5251.

- 24. Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., Deng, Q., Chu, Y., Dong, P., Chen, C., Wang, Z., Xia, Z., and Yang, C., (2024), In situ and real-time monitoring the chemical and thermal evolution of lithium-ion batteries with single-crystalline Ni-rich layered oxide cathode, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 63(18), e202401716.

- 25. Li, H., Wei, F., Li, Y., Yu, M., Zhang, Y., Liu, L., and Liu, Z., (2021), Optical fiber sensor based on upconversion nanoparticles for internal temperature monitoring of Li-ion batteries, Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 9(41), 14757-14765.

- 26. Yang, G., Leitão, C., Li, Y., Pinto, J., and Jiang, X., (2013), Real-time temperature measurement with fiber bragg sensors in lithium batteries for safety usage, Measurement, 46(9), 3166-3172.

- 27. Ren, X., Gao, J., Shi, H., Huang, L., Zhao, S., and Xu, S., (2021), A highly sensitive all-fiber temperature sensor based on the enhanced green upconversion luminescence in Lu2MoO6: Er3+/yb3+ phosphors by co-doping Li+ ions, Optik, 227, 166084.

- 28. Rowe D. M.. 2005. Thermoelectrics handbook: Macro to nano. CRC Press.

- 29. AlWaaly, A. A., Paul, M. C., and Dobson, P. S., (2015), Effects of thermocouple electrical insulation on the measurement of surface temperature, Applied Thermal Engineering, 89, 421-431.

- 30. Feng, X., Fang, M., He, X., Ouyang, M., Lu, L., Wang, H., and Zhang, M., (2014), Thermal runaway features of large format prismatic lithium ion battery using extended volume accelerating rate calorimetry, Journal of Power Sources, 255, 294-301.

- 31. Li, Z., Zhang, J., Wu, B., Huang, J., Nie, Z., Sun, Y., An, F., and Wu, N., (2013), Examining temporal and spatial variations of internal temperature in large-format laminated battery with embedded thermocouples, Journal of Power Sources, 241, 536-553.

- 32. Dey, S., Biron, Z. A., Tatipamula, S., Das, N., Mohon, S., Ayalew, B., and Pisu, P., (2016), Model-based real-time thermal fault diagnosis of lithium-ion batteries, Control Engineering Practice, 56, 37-48.

- 33. Waldmann, T., Gorse, S., Samtleben, T., Schneider, G., Knoblauch, V., and Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M., (2014), A mechanical aging mechanism in lithium-ion batteries, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 161(10), A1742.

- 34. Waldmann, T., and Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M., (2015), In-operando measurement of temperature gradients in cylindrical lithium-ion cells during high-current discharge, ECS Electrochemistry Letters, 4(1), A1.

- 35. Anthony, D., Wong, D., Wetz, D., and Jain, A., (2017), Non-invasive measurement of internal temperature of a cylindrical Li-ion cell during high-rate discharge, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 111, 223-231.

- 36. Drake, S. J., Martin, M., Wetz, D. A., Ostanek, J. K., Miller, S. P., Heinzel, J. M., and Jain, A., (2015), Heat generation rate measurement in a Li-ion cell at large C-rates through temperature and heat flux measurements, Journal of Power Sources, 285, 266-273.

- 37. Zhang, G., Cao, L., Ge, S., Wang, C.-Y., Shaffer, C. E., and Rahn, C. D., (2014), In situ measurement of radial temperature distributions in cylindrical Li-ion cells, Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 161(10), A1499.

- 38. Childs, P. R., Greenwood, J., and Long, C., (2000), Review of temperature measurement, Review of Scientific Instruments, 71(8), 2959-2978.

- 39. Koshkouei, M. J., Saniee, N. F., and Barai, A., (2024), Thermocouple selection and its influence on temperature monitoring of lithium-ion cells, Journal of Energy Storage, 92, 112072.

- 40. Beguš, S., Bojkovski, J., Drnovšek, J., and Geršak, G., (2014), Magnetic effects on thermocouples, Measurement Science and Technology, 25(3), 035006.

- 41. Inyushkin, A., Leicht, K., and Esquinazi, P., (1998), Magnetic field dependence of the sensitivity of a type E (chromel-constantan) thermocouple, Cryogenics, 38(3), 299-304.

- 42. Smalcerz, A., and Przylucki, R., (2013), Impact of electromagnetic field upon temperature measurement of induction heated charges, International Journal of Thermophysics, 34(4), 667-679.

- 43. Shir, F., Mavriplis, C., and Bennett, L. H., (2005), Effect of magnetic field dynamics on the copper‐constantan thermocouple performance, Instrumentation Science & Technology, 33(6), 661-671.

- 44. Wang, P., Zhang, X., Yang, L., Zhang, X., Yang, M., Chen, H., and Fang, D., (2016), Real-time monitoring of internal temperature evolution of the lithium-ion coin cell battery during the charge and discharge process, Extreme Mechanics Letters, 9, 459-466.

- 45. Yu, Y., Vergori, E., Worwood, D., Tripathy, Y., Guo, Y., Somá, A., Greenwood, D., and Marco, J., (2021), Distributed thermal monitoring of lithium ion batteries with optical fibre sensors, Journal of Energy Storage, 39, 102560.

- 46. Yu, Y., Vergori, E., Maddar, F., Guo, Y., Greenwood, D., and Marco, J., (2022), Real-time monitoring of internal structural deformation and thermal events in lithium-ion cell via embedded distributed optical fibre, Journal of Power Sources, 521, 230957.

- 47. Amietszajew, T., Fleming, J., Roberts, A. J., Widanage, W. D., Greenwood, D., Kok, M. D., Pham, M., Brett, D. J., Shearing, P. R., and Bhagat, R., (2019), Hybrid thermo‐electrochemical in situ instrumentation for lithium‐ion energy storage, Batteries & Supercaps, 2(11), 934-940.

- 48. Fleming, J., Amietszajew, T., Charmet, J., Roberts, A. J., Greenwood, D., and Bhagat, R., (2019), The design and impact of in-situ and operando thermal sensing for smart energy storage, Journal of Energy Storage, 22, 36-43.

- 49. Vincent, T. A., Hasa, I., Gulsoy, B., Sansom, J. E., and Marco, J., (2022), Battery cell temperature sensing towards smart sodium-ion cells for energy storage applications, Proceedings of the IEEE 16th International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics, and Power Engineering, 1-6.

- 50. Lee, C.-Y., Lee, S.-J., Hung, Y.-M., Hsieh, C.-T., Chang, Y.-M., Huang, Y.-T., and Lin, J.-T., (2017), Integrated microsensor for real-time microscopic monitoring of local temperature, voltage and current inside lithium ion battery, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 253, 59-68.

- 51. Zhu, S., Han, J., An, H.-Y., Pan, T.-S., Wei, Y.-M., Song, W.-L., Chen, H.-S., and Fang, D., (2020), A novel embedded method for insitu measuring internal multi-point temperatures of lithium ion batteries, Journal of Power Sources, 456, 227981.

- 52. Talplacido, N. C., and Cumming, D. J., (2024), Printed carbon black thermocouple as an in situ thermal sensor for lithium-ion cell, Batteries, 10(3), 78.

- 53. Riddle J. L., Furukawa G. T., Plumb H. H.. 1973. Platinum resistance thermometry. National Bureau of Standards.

- 54. Wu, J., (2018), A basic guide to RTD measurements, Texas Instruments, (Report No. SBAA275). https://docs.ampnuts.ru/ti.com.datasheet/ADS1262/Application_note_SBAA275.PDF.

- 55. Bentley, J., (1984), Temperature sensor characteristics and measurement system design, Journal of Physics E: Scientific Instruments, 17(6), 430.

- 56. Cai, Q., Chen, Y.-C., Tsai, C., and DeNatale, J. F., (2012), Development of a platinum resistance thermometer on the silicon substrate for phase change studies, Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, 22(8.

- 57. Wei, Z., Zhao, J., He, H., Ding, G., Cui, H., and Liu, L., (2021), Future smart battery and management: Advanced sensing from external to embedded multi-dimensional measurement, Journal of Power Sources, 489, 229462.

- 58. Jones, C. M., Sudarshan, M., Garcia, R. E., and Tomar, V., (2023), Direct measurement of internal temperatures of commercially-available 18650 lithium-ion batteries, Sci Rep, 13(1), 14421.

- 59. Gureyev, V. V., and L'vov, A. A., (2007), High accuracy semiautomatic calibration of industrial RTD, Proceedings of the IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Technology Conference, 1-5.

- 60. Otomański, P., Pawłowski, E., and Szlachta, A., (2025), In situ evaluation of the self-heating effect in resistance temperature sensors, Sensors, 25(11), 3374.

- 61. Ling, X., Zhang, Q., Xiang, Y., Chen, J. S., Peng, X., and Hu, X., (2023), A Cu/Ni alloy thin-film sensor integrated with current collector for in-situ monitoring of lithium-ion battery internal temperature by high-throughput selecting method, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 214, 124383.

- 62. Choi, W., Shin, H.-C., Kim, J. M., Choi, J.-Y., and Yoon, W.-S., (2020), Modeling and applications of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (eis) for lithium-ion batteries, Journal of Electrochemical Science and Technology, 11(1), 1-13.

- 63. Macdonald J. R., Johnson W. B., Raistrick I., Franceschetti D., Wagner N., McKubre M., Macdonald D., Sayers B., Bonanos N., Steele B.. 2018. Impedance spectroscopy: Theory, experiment, and applications. John Wiley & Sons.

- 64. Lazanas, A. C., and Prodromidis, M. I., (2023), Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy─ a tutorial, ACS Measurement Science Au, 3(3), 162-193.

- 65. Srinivasan, R., Carkhuff, B. G., Butler, M. H., and Baisden, A. C., (2011), Instantaneous measurement of the internal temperature in lithium-ion rechargeable cells, Electrochimica Acta, 56(17), 6198-6204.

- 66. Schmidt, J. P., Arnold, S., Loges, A., Werner, D., Wetzel, T., and Ivers-Tiffée, E., (2013), Measurement of the internal cell temperature via impedance: Evaluation and application of a new method, Journal of Power Sources, 243, 110-117.

- 67. Richardson, R. R., Ireland, P. T., and Howey, D. A., (2014), Battery internal temperature estimation by combined impedance and surface temperature measurement, Journal of Power Sources, 265, 254-261.

- 68. Ströbel, M., Pross-Brakhage, J., Kopp, M., and Birke, K. P., (2021), Impedance based temperature estimation of lithium ion cells using artificial neural networks, Batteries, 7(4), 85.

- 69. Blömeke, A., Kappelhoff, O., Wasylowski, D., Ringbeck, F., and Sauer, D. U., (2024), Open source online electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data analytics tool, Journal of Power Sources, 615.

- 70. Mc Carthy, K., Gullapalli, H., and Kennedy, T., (2022), Real-time internal temperature estimation of commercial Li-ion batteries using online impedance measurements, Journal of Power Sources, 519, 230786.

- 71. Wang, L., Lu, D., Song, M., Zhao, X., and Li, G., (2020), Instantaneous estimation of internal temperature in lithium‐ion battery by impedance measurement, International Journal of Energy Research, 44(4), 3082-3097.

- 72. Wenjie, F., Zhibin, Z., Ming, D., and Ming, R., (2021), On-line estimation method for internal temperature of lithium-ion battery based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, Proceedings of the IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), 247-251.

- 73. Meddings, N., Heinrich, M., Overney, F., Lee, J.-S., Ruiz, V., Napolitano, E., Seitz, S., Hinds, G., Raccichini, R., and Gaberšček, M., (2020), Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to commercial Li-ion cells: A review, Journal of Power Sources, 480, 228742.

- 74. Lin, C.-K., Ren, Y., Amine, K., Qin, Y., and Chen, Z., (2013), In situ high-energy X-ray diffraction to study overcharge abuse of 18650-size lithium-ion battery, Journal of Power Sources, 230, 32-37.

- 75. Liu, Q., He, H., Li, Z.-F., Liu, Y., Ren, Y., Lu, W., Lu, J., Stach, E. A., and Xie, J., (2014), Rate-dependent, Li-ion insertion/deinsertion behavior of LiFePO4 cathodes in commercial 18650 LiFePO4 cells, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 6(5), 3282-3289.

- 76. Moriya, M., Miyahara, M., Hokazono, M., Sasaki, H., Nemoto, A., Katayama, S., Akimoto, Y., Hirano, S.-i., and Ren, Y., (2014), High-energy X-ray powder diffraction and atomic-pair distribution-function studies of charged/discharged structures in carbon-hybridized Li2MnSiO4 nanoparticles as a cathode material for lithium-ion batteries, Journal of Power Sources, 263, 7-12.

- 77. Doeff, M. M., Chen, G., Cabana, J., Richardson, T. J., Mehta, A., Shirpour, M., Duncan, H., Kim, C., Kam, K. C., and Conry, T., (2013), Characterization of electrode materials for lithium ion and sodium ion batteries using synchrotron radiation techniques, Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE, (81), 50594.

- 78. Lin, F., Liu, Y., Yu, X., Cheng, L., Singer, A., Shpyrko, O. G., Xin, H. L., Tamura, N., Tian, C., and Weng, T.-C., (2017), Synchrotron X-ray analytical techniques for studying materials electrochemistry in rechargeable batteries, Chemical Reviews, 117(21), 13123-13186.

- 79. Heenan, T., Mombrini, I., Llewellyn, A., Checchia, S., Tan, C., Johnson, M., Jnawali, A., Garbarino, G., Jervis, R., and Brett, D., (2023), Mapping internal temperatures during high-rate battery applications, Nature, 617(7961), 507-512.

- 80. Yu, Y., Vergori, E., Maddar, F., Guo, Y., Greenwood, D., and Marco, J., (2022), Real-time monitoring of internal structural deformation and thermal events in lithium-ion cell via embedded distributed optical fibre, Journal of Power Sources, 521, 230957.

- 81. Yu, X., Feng, Z., Ren, Y., Henn, D., Wu, Z., An, K., Wu, B., Fau, C., Li, C., and Harris, S. J., (2018), Simultaneous operando measurements of the local temperature, state of charge, and strain inside a commercial lithium-ion battery pouch cell, Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 165(7), A1578.

- 82. Vennam, G., Tanim, T. R., and Dufek, E. J., (2023), Synchrotron methods to measure internal temperature of lithium-ion batteries, Joule, 7(7), 1411-1414.

- 83. Luo, X., and Wang, H., (2022), A high temporal-spatial resolution temperature sensor for simultaneous measurement of anisotropic heat flow, Materials, 15(15), 5385.

- 84. Diehl, W., (1984), Platinum thin film resistors as accurate and stable temperature sensors, (Report No. NASA-TM-77728), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19850002015.

- 85. Nicholas, J., and White, D. R., (2002), Traceable temperatures: An introduction to temperature measurement and calibration, 2nd edn, Measurement Science and Technology, 13(10), 1651-1651.

- 86. Spinner, N. S., Love, C. T., Rose-Pehrsson, S. L., and Tuttle, S. G., (2015), Expanding the operational limits of the single-point impedance diagnostic for internal temperature monitoring of lithium-ion batteries, Electrochimica Acta, 174, 488-493.

- 87. Finegan, D. P., Quinn, A., Wragg, D. S., Colclasure, A. M., Lu, X., Tan, C., Heenan, T. M., Jervis, R., Brett, D. J., and Das, S., (2020), Spatial dynamics of lithiation and lithium plating during high-rate operation of graphite electrodes, Energy & Environmental Science, 13(8), 2570-2584.

- 88. Finegan, D. P., Scheel, M., Robinson, J. B., Tjaden, B., Hunt, I., Mason, T. J., Millichamp, J., Di Michiel, M., Offer, G. J., and Hinds, G., (2015), In-operando high-speed tomography of lithium-ion batteries during thermal runaway, Nature Communications, 6(1), 6924.

- 89. Marschilok, A. C., Bruck, A. M., Abraham, A., Stackhouse, C. A., Takeuchi, K. J., Takeuchi, E. S., Croft, M., and Gallaway, J. W., (2020), Energy dispersive X-ray diffraction (edxrd) for operando materials characterization within batteries, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 22(37), 20972-20989.

- 90. Vaughan, G. B., Baker, R., Barret, R., Bonnefoy, J., Buslaps, T., Checchia, S., Duran, D., Fihman, F., Got, P., and Kieffer, J., (2020), ID15A at the ESRF-a beamline for high speed operando X-ray diffraction, diffraction tomography and total scattering, Synchrotron Radiation, 27(2), 515-528.

- 91. Yoneyama, A., Iizuka, A., Fujii, T., Hyodo, K., and Hayakawa, J., (2018), Three-dimensional X-ray thermography using phase-contrast imaging, Scientific Reports, 8(1), 12674.

Biography

- Soyoung Park

Researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Hanyang University. Her research interest is internal temperature of batteries.

- Woosung Park

Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Hanyang University. His research interest is heat and matter.